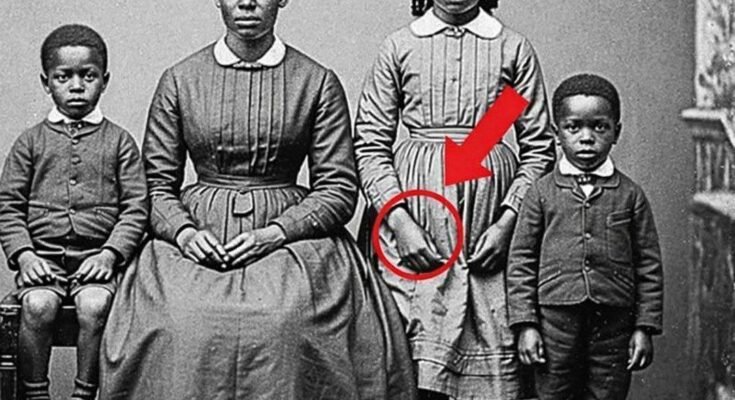

It Was Just a Simple Family Photograph Dating from 1872, Until a Detail on a Woman’s Hand Caught the Eye

In a dusty attic of an old Victorian house, tucked between yellowed newspapers and fading letters, lay a simple family photograph. Its edges were curled, and the corners were frayed, but the faces in the image were remarkably clear. Taken in 1872, the photograph depicted a family posing stiffly for the camera, as was customary in the era of long exposure times and formal portraits.

At first glance, it was unremarkable—a father in a bowler hat, a mother in a high-collared dress, and three children lined up obediently in their Sunday best. But sometimes, it’s the smallest details that tell the biggest stories. And in this case, it was a tiny detail on the woman’s hand that would eventually capture the attention of historians, photographers, and amateur sleuths alike.

The photograph was discovered by Emma Crawford, a local history enthusiast, while helping her grandmother sort through old family possessions. “It was just one of those things you come across and think, ‘Oh, another old photo,’” Emma recalled. “But something made me pause. The mother’s hand—it looked… different.”

It wasn’t the jewelry. She wore a modest ring, typical of the period. Nor was it a pose—hands were usually folded neatly or clasped in formal portraits. But the subtle curve of her fingers and the unusual texture on the palm hinted at something unusual. Emma, curious and meticulous, scanned the photograph again under better lighting and even used a magnifying glass. That’s when she noticed it: a tiny, almost imperceptible pattern etched into the skin of her hand.

It looked like delicate tattooing, which seemed entirely out of place for a Victorian housewife in rural England.

Tattoos in the 19th Century: A Rare Sight

To understand why this detail was striking, it helps to know a bit about the history of tattoos. By the late 1800s, tattoos in Europe were almost exclusively associated with sailors, criminals, and the working class. Aristocrats and middle-class women would rarely have any form of tattooing; it was considered improper and even scandalous.

So, seeing what appeared to be intricate markings on the hand of a woman dressed in the most conservative fashion raised immediate questions:

Who was she?

Why did she have this marking?

Was it a tattoo at all, or some kind of skin condition, birthmark, or artistic illusion caused by photography?

Emma knew she was holding something unusual, and she wanted answers.

Researching the Mystery

Determined to find out more, Emma took the photograph to the local historical society. She showed it to Dr. Robert Lanning, a historian specializing in Victorian life and customs. Dr. Lanning was immediately intrigued. “Victorian photography captured everything—every fold of clothing, every wrinkle, even textures that weren’t visible to the naked eye,” he explained. “If that is indeed a tattoo, it would be very unusual for a woman of her apparent social standing and time period.”

Together, they began to research the family in the photograph. Census records, birth certificates, and marriage registries helped them identify the woman as Margaret Whitaker, a schoolteacher living in a small village outside Manchester. Her husband, Thomas, was a merchant, and the children were all enrolled in local schools. On paper, she led a life that was conservative, quiet, and seemingly ordinary.

Nothing in the public record hinted at any unusual hobbies, travels, or social rebellion. Yet the photograph told a different story.

Clues in the Hand

As experts studied the photograph more closely, several things became apparent:

The markings were symmetrical, suggesting deliberate design rather than an accident or skin condition.

The pattern resembled henna designs, with small floral and geometric motifs.

Henna tattoos were occasionally used in Victorian Europe, but mostly by women who had traveled to the Middle East, India, or North Africa—far from rural England.